Gaia is 45 Years Old

Earth is 4.54 billion years old.

That number is almost meaningless to us. Our brains evolved to track seasons, to remember faces, to plan for next week's hunt. We have no neural architecture for comprehending billions of anything. The number just sits there, inert, failing to move us.

So let's try something different. Let's compress Earth's entire history into a human lifetime. Divide by 100 million, and our planet becomes a 45-year-old woman. Let's call her Gaia.

Gaia has had a rich and beautiful life.

The Early Years

For her first seven years, Gaia was bombarded by asteroids and comets, the violent leftovers of the solar system's formation. Her surface was molten, her skies poison. Not a great childhood.

But life is stubborn. By the time Gaia turned seven (about 3.8 billion years ago), the first single-celled organisms appeared. For the next seventeen years of her life, from age 7 to 24, life remained microscopic. Bacteria. Archaea. Simple cells doing simple things, slowly transforming her atmosphere, preparing the stage.

Around age 21, the Great Oxidation Event began. Cyanobacteria had been quietly photosynthesizing for eons, and their oxygen waste product finally accumulated enough to transform Earth's atmosphere. This was, from one perspective, the first great pollution event. Oxygen was toxic to most existing life. But it also made complex life possible.

Growing Up

Gaia hit a major milestone around age 40: the Cambrian Explosion, when complex multicellular life burst onto the scene in an evolutionary riot of forms and experiments. Eyes, shells, predators, prey. The fossil record suddenly fills with creatures we'd almost recognize.

At 40.7 years old, plants colonized land. At 43, the first mammals appeared. Small, furry, insignificant things scurrying beneath the feet of dinosaurs.

Then, at 44 years and about 8 months (66 million years ago), an asteroid struck what is now the Yucatan Peninsula. The dinosaurs, who had dominated for over two years of Gaia's life, were gone within weeks.

The mammals inherited a shattered world and got to work.

Yesterday Afternoon

Here's where it gets humbling.

Modern humans (Homo sapiens) appeared approximately 315,000 years ago. On Gaia's timeline, that's about 27 hours ago. A little over one day.

We showed up yesterday afternoon.

Everything we think of as human history, every empire, every prophet, every war, every love story, every song ever sung, has happened in the last day of Gaia's 45-year life.

Let me break down some milestones:

| Event | Years Ago | Gaia's Time |

|---|---|---|

| Homo sapiens appear | 315,000 | ~27 hours ago |

| Out of Africa migration | 70,000 | ~6 hours ago |

| Agriculture invented | 12,000 | ~4 seconds ago |

| Writing invented | 5,000 | ~1.6 seconds ago |

| Watt's steam engine | 1763 | ~83 milliseconds ago |

| Internet (ARPANET) | 1969 | ~18 milliseconds ago |

| World Wide Web | 1989 | ~12 milliseconds ago |

| Bitcoin genesis block | 2009 | ~5 milliseconds ago |

Read that again. Agriculture, the foundation of civilization, was invented four seconds ago. The Industrial Revolution began 83 milliseconds ago. The entire digital age, everything from mainframes to smartphones to AI, has unfolded in the last 18 milliseconds of Gaia's life.

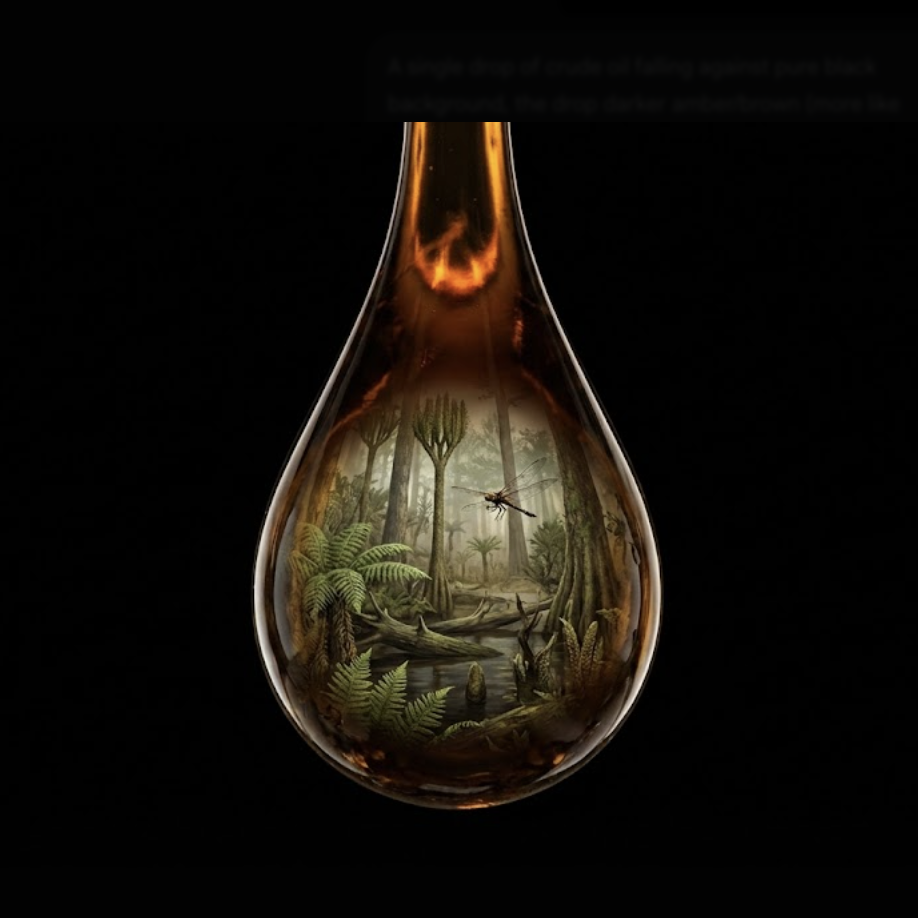

The Carboniferous Gift

Now let's talk about something Gaia did in her early forties.

Between ages 42 and 43 (roughly 359 to 299 million years ago), during what we call the Carboniferous Period, massive forests covered the land. Trees unlike anything alive today, towering lycopsids and tree ferns in vast swamps. When these trees died in these waterlogged, oxygen-poor environments, they didn't fully decompose. Instead, the dead organic matter accumulated, was buried by sediment, and was slowly cooked by geological heat and pressure over millions of years.

They became coal.

Scientists once thought this happened because fungi hadn't yet evolved the ability to break down lignin (the tough polymer in wood). But more recent research suggests a different story: the unique combination of everwet tropical conditions and extensive depositional systems during the assembly of the supercontinent Pangea created ideal conditions for coal formation.1 The exact mechanisms are still debated, but the result is undeniable: vast carbon stores, buried deep underground.

Oil and natural gas formed similarly, mostly from marine organisms during the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods, when Gaia was 43 to 44 years old.

In other words, Gaia spent millions of years slowly sequestering carbon. Drawing it out of the atmosphere, burying it underground, locking it away. This process cooled the planet, stabilized the climate, and created the conditions that allowed complex life, and eventually us, to thrive.

The Blink of an Eye

Now here's the part that should stop you cold.

We discovered those buried carbon stores about 80 milliseconds ago in Gaia's time. Since commercial drilling began in 1850, humanity has extracted and burned approximately 1.5 trillion barrels of crude oil.2 Current proven reserves sit at roughly another 1.5–1.7 trillion barrels.3 We've consumed about half of what's economically accessible, in the span of a single heartbeat of geological time.

We've released carbon that took Gaia millions of years to sequester. In milliseconds.

Consider what this means. We've released enough carbon to measurably warm the planet, acidify the oceans, and, according to the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), drive extinction rates to levels "at least tens to hundreds of times higher than the average over the past 10 million years."4 Many scientists argue we are witnessing the beginning of what some call a sixth mass extinction, though the terminology remains debated among researchers.5

Will She Recover?

Here's the strange comfort: Gaia will be fine.

The planet has survived far worse. The Permian-Triassic extinction killed 96% of marine species, and life bounced back. Asteroid impacts, supervolcanic eruptions, snowball Earth events where ice covered the globe from pole to pole. Gaia weathered them all. She'll weather this too.

But the current biosphere? The specific arrangement of ecosystems, species, and climate patterns that we depend on? That's a different question.

What we're doing isn't threatening the planet. We're threatening ourselves.

And we're doing it at a pace that Gaia has never experienced before. Previous climate shifts unfolded over thousands or millions of years. Life had time to migrate, adapt, evolve. We're forcing comparable changes in decades.

Will Gaia create new fossil fuels? Technically, yes. The processes that made coal and oil are still happening in places like peat bogs and ocean floors. But at geological rates. It would take Gaia another two to three years (200 to 300 million actual years) to rebuild comparable reserves.

We won't be around to use them.

The Complexity

I want to be honest about something: the path forward is not simple.

Transitioning away from fossil fuels involves real trade-offs. It requires massive infrastructure investment, political will across nations with competing interests, and solutions for communities whose livelihoods depend on extraction industries. There are reasonable debates about pace, about which technologies to prioritize, about how to balance development needs in the Global South with emissions reduction.

Consider just one example: the role of nuclear power. Some climate scientists and environmentalists argue it's essential, a proven, scalable, zero-carbon energy source that can provide baseload power when the sun isn't shining and the wind isn't blowing. Others point to waste storage challenges, high construction costs, and the decades-long timelines to bring new plants online, arguing that renewables plus storage can do the job faster and cheaper. Both sides cite legitimate evidence. The debate is real, and reasonable people disagree.

Similar debates exist around carbon pricing mechanisms, the pace of fossil fuel phase-outs, the role of natural gas as a "bridge fuel," and how to handle the economic disruption in coal-dependent regions. The scientists who study this most closely generally agree on the destination (a low-carbon economy) while debating the best routes to get there. The IPCC's scenarios range from manageable warming to catastrophic, depending largely on choices made in the next two decades.6

This isn't about moral purity. It's about probability and risk management on a civilizational scale.

The Choice

And yet.

In the last few milliseconds of Gaia's life, something new has happened. For the first time in 4.54 billion years, one of her species has become aware of her story. We can read the rocks and understand what happened. We can model the future and see where we're headed. We have the technology to power our civilization without burning ancient carbon.

We're the first species in Gaia's entire 45-year life that can choose.

Previous extinctions were imposed by asteroids, volcanoes, or chemistry. But we're causing this one, which means we can also stop it. We have solar panels and wind turbines and batteries and nuclear plants. We have electric vehicles and heat pumps and sustainable agriculture. We have the economic and technological tools to transition away from fossil fuels within a generation.

The physicist David Deutsch offers a framework for understanding our situation: "Problems are inevitable," he writes in The Beginning of Infinity. "But problems are soluble."7 This isn't wishful thinking. It's a recognition that there is no law of nature preventing us from solving our problems. When we fail, it's not because the universe is hostile or the gods are angry. It's because we don't yet know enough. Climate change is a problem. And problems, by their nature, are soluble, given sufficient knowledge.

The question isn't whether it's possible. The question is whether we'll do it.

A New Second

If we stay on our current trajectory, the next 30 milliseconds of Gaia's life (the next century of ours) will see significant warming, rising seas, ecosystem disruption, and biodiversity loss. Not the end of life on Earth, but perhaps the end of the stable, abundant world that allowed human civilization to flourish.

But that's not the only path.

Throughout history, most human civilizations have been what Deutsch calls "static societies," cultures that sustained themselves by discouraging change, suppressing innovation, and worshipping tradition. When such societies faced novel challenges, they lacked the means to respond. They collapsed, like Easter Island, or stagnated for millennia. The knowledge that could have saved them was never created because their social structures made its creation impossible.

Our civilization is different. Not because we're smarter, but because we have something rare in human history: a tradition of criticism, of questioning, of solving problems through conjecture and testing rather than deference to authority. This is what Deutsch calls the "beginning of infinity," the recognition that progress is not just possible but unbounded, limited only by our willingness to keep solving problems.

The next second of Gaia's life could be the moment one species grew up. The moment we stopped being unconscious consumers and started being conscious stewards. The moment we learned to power our civilization with the sun and wind and atoms instead of burning our host's ancient savings.

We've been here for about a day of Gaia's life. We've been industrial for less than 100 milliseconds. We've been aware of the problem for perhaps 20 milliseconds, since the first climate scientists raised the alarm in the 1960s.

That's not much time. But it's enough.

As Deutsch reminds us, "Knowledge alone converts landscapes into resources." The primeval Earth, for all its buried coal and oil, contained not a single idea. The resources were always there. It was human knowledge that made them useful. And it will be human knowledge that moves us beyond them.

The next second is unwritten. And for the first time in 4.54 billion years, one of Gaia's children gets to choose what happens next.

What will we choose?

What You Can Do

If this perspective moved you, here are a few concrete next steps:

-

Learn more: The IPCC's Summary for Policymakers offers an accessible overview of climate science. For biodiversity, see the IPBES Global Assessment.

-

Calculate your footprint: Tools like the EPA's Carbon Footprint Calculator help you understand where your personal emissions come from and where you can make changes.

-

Vote and advocate: Individual choices matter, but systemic change requires policy. Support candidates who prioritize climate action, and consider joining organizations working on energy transition. Citizens' Climate Lobby focuses on bipartisan carbon pricing policy, while 350.org organizes grassroots climate campaigns globally.

-

Talk about it: Research shows that one of the biggest barriers to climate action is the perception that "nobody else cares." Simply discussing these issues with friends and family makes concern visible and gives others permission to care too.

Further Reading

- David Deutsch, The Beginning of Infinity: Explanations That Transform the World (2011)

- Elizabeth Kolbert, The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History (2014)

- Peter Brannen, The Ends of the World: Volcanic Apocalypses, Lethal Oceans, and Our Quest to Understand Earth's Past Mass Extinctions (2017)

- Vaclav Smil, Energy and Civilization: A History (2017)

If you found this perspective useful, feel free to share it with someone who might appreciate thinking about time differently.

Footnotes

-

Nelsen, M.P., et al. (2016). "Delayed fungal evolution did not cause the Paleozoic peak in coal production." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(9), 2442-2447. doi:10.1073/pnas.1517943113 ↩

-

Estimates vary, but approximately 1.5 trillion barrels have been produced since 1900. See: Visualizing Energy, "The history of oil production in the United States" (2024); OilPrice.com analysis of BP Statistical Review data. ↩

-

OPEC Annual Statistical Bulletin 2024 reports world proven crude oil reserves at 1,570 billion barrels as of end-2023. ↩

-

IPBES (2019). Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. ipbes.net ↩

-

Cowie, R.H., et al. (2022). "The Sixth Mass Extinction: fact, fiction or speculation?" Biological Reviews, 97(2), 640-663. doi:10.1111/brv.12816 ↩

-

IPCC (2023). AR6 Synthesis Report: Climate Change 2023. ipcc.ch ↩

-

Deutsch, David (2011). The Beginning of Infinity: Explanations That Transform the World. Viking. See especially Chapter 9, "Optimism," and Chapter 17, "Unsustainable." ↩

Discussion

Comments are powered by GitHub Issues. Join the conversation by opening an issue.

⊹Add Comment via GitHub